- Yesterday …

- Okay, maybe it was Saturday.

- Yeah, definitely Saturday.

- We went to Mi Tierra for dinner.

- Had fajita leftovers.

- They were not my leftovers, but I was told I could have them for lunch today.

- Which is nice.

- Nice to not have to worry about spending $17 for lunch downtown, you know?

- I had my bag slung around my chest, my coffee in one hand, the styrofoam container with the fajitas in the other.

- (Who still uses styrofoam?)

- (Well, lookie there. Apparently “Styrofoam” is a brand name like Kleenex or Xerox.)

- (No, you environment killing thing, I will not give you a capital S.)

- Scanned in, went to pull open the big glass door to the 14th floor …

- Which slipped.

- And caught the fajita container and my arm, flinging it from my grasp.

- Fajitas everywhere.

- Everywhere being mostly the floor.

- And my hand.

- Which after multiple washings still smells like fajitas.

- Sigh.

- Apologies to the cleaning staff.

- My fault.

- How’s your Monday?

- Mini fiction:

- He nodded to the woman behind the security desk as he entered the building.

- “Good morning,” she said.

- He echoed the greeting, lamented for the moment he did not know her name. Well, if it were really a she? It looked like a she, but he knew it was one of the latest bots from Boston Dynamics. Probably had a model designation and not a real name like Sally or Veronica. Maybe he’d give it a name. Later, though. The timeclock waits for no one, however, and he needed to get upstairs for a meeting … which started in four minutes. At least it was a Zoom meeting.

- He stopped in front of the elevator bank, mashed the Up button with the pointer finger on his right hand while the rest clung to the coffee tumbler. His other hand held a small square box of “gourmet” donut holes.

- The button’s yellow-orangish light lit up.

- He leaned around his left arm to check the time.

- Two minutes.

- Ugh.

- The elevator beeped. He fought the urge to step forward, reviewing stock footage of all the times he tried to rush onto the opening elevator while people tried to get out. All the awkward apologies to people he didn’t know.

- The doors opened.

- No one got out.

- He stepped on, looked at the bank of floor buttons and the card scanner.

- Oh, right.

- He fumbled with the ID lanyard, snaking his thumb behind the ribbon to extend the card toward the scanner. He wondered how ridiculous he looked if the security guard happened to be watching from their console.

- Card mashed against the scanner. The light turned green. He dropped the lanyard and thumbed the button for his floor, then stepped toward the back of the elevator, started to rehearse what he might need to say in the Zoom meeting.

- Then realized the elevator had not moved.

- He glared at the floor buttons. None were lit.

- He sighed, loudly.

- “Work, you stupid thing.”

- He repeated the card scan/button process. Why did they even have to scan a card still? Couldn’t they code these things with biometrics? Or even scan your card in your pocket? Why the old school tech? Maybe the building supes spent all the money on Sally.

- He refocused.

- Again, all the proper lights lit. Again, he stepped back, this time keeping his eyes on the buttons.

- The lights, which lit for a moment, went off.

- “Seriously?”

- He repeated the watch dance.

- Late.

- Officially.

- He stepped forward, tapped the “open door” button.

- Nothing happened.

- “C’mon, you dumb thing. Work!”

- Talking to himself on a Monday morning while trapped in an elevator …

- The elevator dinged, lurched upward for a second, then stopped, bouncing.

- He struggled to keep his coffee in his hand as his arm whipped out to catch the wall for balance.

- He glanced around, looking for a camera.

- “Help?”

- Again, it lurched upward, stopped. Lurch. Stop.

- He crouched back against the wall, waited. Counted to 100. Why he counted to 100 he didn’t really know, but it seemed a reasonable amount of time to make sure everything was … stable.

- He stood, stepped toward the buttons, then repeated the card swipe process and reselected his floor. The buttons lit up like they were supposed to. The elevator began to climb.

- “Thanks for nothing, dumb elevator.”

- He felt an increase in upward velocity in his knees, which flexed a bit. He flicked his eyes to the floor indicator as his floor came and went.

- He gritted his teeth.

- The elevator stopped at the top floor.

- He waited for the doors to open, visualized the door to the stairs.

- The doors did not open.

- He leaned forward, mashed the “open” button.

- Nothing happened.

- “Open the doors, you piece of junk!”

- He stomped on the floor.

- Which opened. He slipped into the dark of the elevator shaft, coffee and donuts flying from his hands as he flailed. As he fell, he looked up and watched the yellow light of the elevator vanish.

- Mondays, he thought.

- …

- End.

- Yeah, I dunno. That’s what popped into my head this morning getting on the elevator here at the Arvest Tower.

- I have never written list-based fiction before now. Nor let anyone read that kind of thing without massive edits. That’s a first draft. Heh.

- Also, that was before the Fajita Fiasco of March 2025.

- Also, I have to go read the comments from the Millennials in Friday’s list. I see there are new ones, but I have not gotten there yet. Been a busy Monday, even without the fajitas.

- Also, this was all written to Iron Maiden’s Somewhere in Time (album, not just the song.)

- Dunno, man. I listened to another of their albums over the weekend, Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, which is one of those concept albums.

- I have memories of the day that came out when I was in junior high.

- Sorry. Middle school.

- I really haven’t listened to Maiden since seeing them in Tulsa a handful of years ago.

- They played too much of their new stuff, which stinks.

- Purged them from my system for a while.

- Okay.

- I’m out.

- You have a Monday.

- Try to keep a good grip on your lunch, right?

- Stay safe!

Category: Fiction

-

Elevator Doors

-

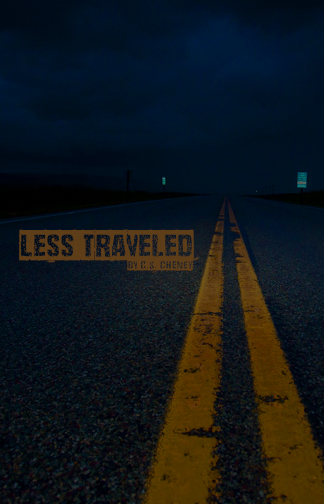

Less Traveled (edited)

Calvin, in a downpour, in the dark, outdrove his headlights. If an animal wandered into the road, he would have zero seconds to avoid splattering it across the pavement. The wipers provided a slideshow, and his eyes strained, tracing the broken line of yellow rectangles.

He’d forgone passing a semi so he could watch its taillights and know when the turns on the narrow road were coming. He made himself blink and rolled his shoulders.

He looked out the side window. Past the tops of whatever dead and dried crop populated the fields, right at the edge of the light, the dark was absolute. It made him uneasy.

“That’s the kind of blackness that made us afraid of the dark,” he said.

“Hmm,” she said, not looking up from her phone.

“Look.”

“What?”

“Look how dark it is.”

The rain lessened as they talked. She lowered the phone. “Are we lost?”

To his ears, it sounded a bit accusatory. “I’m just going where the nice lady on the phone tells me.”

The truck lights, further away than the last time he’d looked, vanished around a turn.

“Jesus. You can’t see anything at all,” she said.

“You can sorta see water in the ditches.”

“Those aren’t ditches. That’s a swamp. Where are we again?”

“Mississippi?”

“See. Swamps.” She said it like Bubba said “Shrimps” in Forrest Gump.

They lapsed into silence, and he, squinting into the dark and light and rain, accelerated trying to catch the truck. The needle crept toward 70.

She screamed. He tensed, the wheel jerked, and the SUV swerved on the slick road.

“Em, what the …”

“That was a goddamn clown!”

He nodded, because he’d seen something out of the corner of his eye, white-and-red headed with blues below. More a blur than anything. “Probably a scarecrow, don’t you think?”

“Yeah, maybe,” she said. Then, “No.”

“No?”

“Its head turned.”

“You’re imagining things.”

“I saw it move. I saw it.” Her voice had a bit of hysteria, high and wavering, so he clamped down on what he’d been about to say, waited a breath.

“I mean, no way. Even as a sick joke, that’s extreme. There’s nothing out here,” he said, gesturing to the dark. “We haven’t passed a house or farm or anything in half an hour. Who would do that?”

The next clown materialized in the middle of the road as though by magic. Calvin had time to think, there’s an actual clown in the road as his reflexes cranked the wheel left and mashed the brakes. At 70, and never a nimble beast, the Xterra shot off the road, motor screaming from lack of resistance, flew over the ditch and into the swampy crops. It bounced once, then the front end caught, standing the SUV up on its nose. Airbags punched them in the face. Then it pirouetted and slammed to the ground, headlights streaming back in the direction they’d come.

He tried not to hyperventilate. His face hurt. The sharp bite of gas and oil tweaked his nose. And expanding ring filled his ears. He looked toward Emma. “You okay?”

He pushed the airbag away, unbuckled his seatbelt, and leaned toward her. “Em?” He heard her then, her breaths short, more in than out. Her nose bled onto her lip, blood black in the dim light, but her eyes stared back at the road. He ran his hand across the side of her cheek, tucked a strand of brown hair behind her ear.

“You saw it that time, right?”

He nodded.

“Where did it go?”

He looked back toward the road. No clown. Back to her. “You okay?”

She blinked, slow, then moved her limbs, one after the other, systems check. She touched her face, hissed.

“No, but yeah.” Her gaze went back to the road. “Are we stuck? We need to get out of here.”

He looked back at the road, then down at the dash. He started to turn the key … “Wait. If the engine’s in the water and I start it …” He opened the door and peered down, black water undulating below the bottom of the car.

“What did you say?”

He realized he’d been mumbling. “We’re stuck. We need to get out.”

“Fuck that.”

“We can’t sit here.”

“Call 911.”

“I don’t even know … ” He stopped. Right. Map app. He fished his phone out of his pocket, unlocked it with this thumb. The light made him squint. He expected no service, but it showed a bar and a half. The network wasn’t AT&T, but MTBC, which was weird. The app, still in navigation mode, showed a blue dot indicating their location.

He made a note of it, dialed 911. It rang more too many times before the dispatcher answered.

“What is your emergency?”

“We’ve been in a car accident.”

“What is your name?”

He told her, then gave her his phone number. No, no one appeared to be seriously injured. No, no other cars were involved. She asked for their location.

“Somewhere off Highway 12 between Hollandale and Belzoni, I think. The dot on my map keeps moving.”

“I see.”

And then the dispatcher said nothing, which he thought was odd.

“Hello?” He waited.

Emma said, “What are they doing?”

He shrugged.

She crawled between the seats, bumping his shoulder with her hip.

“What are you doing?”

“Getting a bottle of water.”

The phone squelched in his ear.

“Sir?”

“Yeah. We’re still here.”

“Are your lights off?”

“What?”

“Your headlights. Are they off?”

“No.”

“Turn them off now, please.”

The hell? He turned off the headlights.

“What was the cause of your accident? Did you fall asleep at the wheel? Did someone run you off the road? Did you hydroplane?”

“Someone was standing in the road.”

“Did you collide with this person?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Are you certain?”

“Pretty sure.”

“Was it a clown?”

A wave of sensation cascaded from the top of his head, along his spine and arms, and into his bladder. “Yes.”

“Do you have any weapons?”

“Uh, a pocket knife?”

More silence.

Emma stopped moving in the back seat. He flicked his eyes to the rearview mirror, met hers. “She asked if it was a clown and whether we had any weapons.”

“The fuck?” She looked out the front window. “It is so dark out there, I can’t even see the road.” She glanced at him. “What the hell are they doing,” pointing toward the phone with her chin.

He shrugged again.

“I’m not sitting in this box in the dark and waiting for some psycho in a clown costume to find me.” She turned and leaned over the back seats. He checked her backside out in the mirror.

“Sir?”

“Yes.”

“We need you to stay put. We have officers en route. Would you like to stay on the line until they arrive?”

“No, that’s okay. Do we need to be worried?”

“Can you see the clown now?”

“No.”

“Good. That’s good.”

“Good?”

“If the officers haven’t arrived in 20 minutes, get back to the road and continue in the direction you were previously heading.”

“On foot? This thing isn’t getting out of here without a wrecker. And didn’t you just tell me to stay in the vehicle?”

“Would you like to stay on the line until the officers arrive?”

“Sure?”

He thumbed the phone to speaker, then pressed mute and set it on the dash. Emma climbed into the front, pulling her black backpack. She settled in the seat, clutched the bag to her chest, and resumed staring out the window.

“We’re holding on the line until the officers arrive. The dispatcher seemed to know about the clown.”

“Clowns,” she said, drawing out the S at the end.

“What?”

“There’s no way the second clown was the same as the first. Not unless it’s a magic teleporting clown. Two clowns.” She held up two fingers.

“Jesus.”

“Yeah.”

They stared out into the night. After a bit, she said, “How long has it been?”

He woke up the phone. “We’ve been on the phone for 18 minutes.” He tapped the volume rocker several times, cranking up the sound. They could hear keyboard clicks and squawks from radios in the background.

“Sir, are you still there?”

He unmuted, said, “Yes, we’re still here.”

“Have you seen a patrol car?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Are you sure you’re on Highway 12?”

He switched apps. “That’s what the app says.”

“We have had four officers searching Highway 12 between Hollandale and Belzoni. They have not found you.”

“You had us turn the lights off.”

“And that’s for your protection. You have not seen any traffic on the road? No patrol cars?”

“Nothing.”

“We need to get you moving. Do you have a flashlight?”

He nodded in the dark.

“Sir?”

“Oh, yeah. Sorry. We have a flashlight.”

“What about water? Food?”

“Yes.”

“If you have a tire tool in the back of your vehicle, I would take it. I wish you had a firearm.”

Emma looked at him, eyes wide. He waited.

“You need to get back up on the road and start walking East. If you can get to Belzoni, you’ll be safe.”

“What the hell kind of advice is that?” Emma said. “You’re supposed to be coming to help us.”

“We’re doing everything we can, ma’am. Get walking. Good luck, and God willing, we’ll see you in Belzoni.”

The dispatcher disconnected.

“What the fuck.”

He nodded.

“Get your backpack,” she said.

He nodded again, climbed through the seats and gathered his gear. He wished he had a gun. His brother always traveled with a gun in the car. A Glock of some kind. Kept it stuck between the seats. He grabbed two bottles of water from the cooler, crammed them into the pack. Then he took the beef jerky and a Ziploc full of Oreos. He zipped up the pack, opened the left rear door and stepped down into the muck. The mud and water filled his shoes, pulling at each as he walked to the back of the SUV. He opened the hatch, dug into the tire kit and took out the scratched black tire wrench.

Emma said, “You get the Oreos?”

He walked around to her side of the Xterra, toes up when he stepped so as not to lose a shoe. He opened her door. She reached back across the car and took the keys out of the ignition, hopped out, slammed the door, then beeped on the security system, the sound shrill and loud in the dark.

They slogged their way to the road.

Emma said, “Where do you think it went?”

“I dunno.”

“It is creepy as hell. If it shows up, I’m going to kick its balls up into its head.”

He laughed. “If it has balls.”

He thumbed on his phone and redid the navigation to show how much time it would take to walk to Belzoni. He opted not to tell Emma. They trudged in the mist and rain for another couple of miles before they saw the search beacon, its blue beam circling through the night like a lighthouse.

“Did you hear that?”

“Hear what?” He said, only then realizing Emma had stopped walking.

“Bells.”

“Bells? Like church bells?”

“No, like fucking clown bells.”

Calvin spun a slow circle, squinting into the gloom as though squinting would make his eyes take in more light. Emma stood for a good minute before resuming her walk.

He said, “You think the light is a house?”

“Might be. Why the searchlight? Tractors going to crash into its rocky pasture?”

“Airfield?”

He heard the bells then, behind them and faint. “I heard them that time.”

She nodded. “Give me the tire tool.”

“Why?”

“You have a knife.”

He handed over the tire tool.

“I think it’s behind us.”

The bells jingled again, slightly louder and faster, along with the rasp of a shoe sole. She grabbed his sleeve, started backing down the road. For half an hour, they walked backward down the road, risking glances over their shoulders until they drew even with a driveway. He tugged her to a stop.

A two-track gravel drive curled away above the swampy crops to a house and what looked like a couple of barns. The searchlight rotated three times. No lights in windows, no security light.No dogs. The place looked abandoned.

He started to say something to Emma when the clown showed up, maybe fifty yards down the road. He couldn’t make out its colors, just broad alternating stripes on its legs. He thumbed on the phone light, shined it at the clown. Its eyes glowed like a cat’s.

Emma hefted the tire iron. “Get the hell out of here,” she yelled. The clown smiled, a half-moon gleam in the murk.

They heard a jingle behind them. Calvin spun. He could make out the outline of a person, a bit farther out than the first.

“There another one?”

“Yes.”

“Maybe we should rush one.”

“They haven’t done anything yet. They could be a couple of annoying kids.”

“Annoying kids that ran us off the fucking road.”

He pulled her onto the drive toward the oscillating light and buildings. Their footsteps crunched. He strained to listen for bells.

“This is stupid,” she said. “They’re down at the mouth of the driveway, watching us. This is exactly where they want us to go. We are being herded. This is how stupid people die in horror movies.” She shook his hand off her arm. “You should’ve let me brain one of them while they were apart.”

Calvin kept moving, letting her rant away her nervousness. A farm house with a small concrete porch with four steps sharpened out of the dark. Three unbroken black windows faced out. A swing set with two swings sat in the yard, each seat twisting slightly on its chains. He wondered how hard it really was to kick in a door.

The beacon splayed over the yard like a slow strobe. Emma stood on her tiptoes, then she said, “I don’t see them.”

They crossed the yard, skirting the edge of the swings, climbed the porch. Calvin knocked on the door, the raps echoing and loud. He winced at the sound. The light crawled past twice, then he banged on the door again. He cupped his hands to the sides of his eyes, peeked in through one of the door’s four glass panes. He looked at Emma, shrugged his shoulders.

He tried the knob. Locked. A black rubber mat sat in front of the threshold. He kicked it over with the muddy toes of his shoes. No key. He stepped back to cop show stomp the door.

She said, “What’re you doing?”

He pointed at the door. She rolled her eyes, stepped to the door, knocked out the pane closest to the handle, reached in and unlocked the door.

He said, “Hey, you think …” Her brows furrowed. “… one of us should stay on the porch to watch for the clowns?”

“Okay, I’ll stay out here with the tire iron. You go look for a shotgun.”

“Shotgun?”

“All farms have guns. Yell if you need me.”

Calvin pulled out his phone, thumbed on the flashlight and went in. It reminded him of a circus version of his grandmother’s. Wide-striped wallpaper, alternating in light and dark, plastered the walls and ceiling. Polka-dotted doilies shrouded the end tables and coffee tables. Thick spirals adorned the couch cushions.

He checked each room. No weapons. No clubs. A set more than a home.

“Calvin!” His pulse jumped and he raced back through the house, out onto the porch.

“What?”

Emma pointed with the tire iron.

A line of mowed grass separated the yard from the cropland between the road and the house. Three clowns stood at the edge of the yard, dry, reedy cornstalks coming to their waists.

Calvin took Emma’s hand, led her off the porch and around to the back of the house. He almost ran them into a natural gas fuel tank, thought, maybe we can blow them up. Behind the house, a huge barn squatted beneath the searchlight tower. Two long buildings with low, almost flat roofs stood back and to the left of the barn.

“Those look like chicken houses,” she said. “We head for the barn. Gotta be an axe or something you could kill a clown with in there.”

“You didn’t see the inside of the house.”

“Tell me while we walk. I liked it better when I could see those assholes.” She strode off for the big barn door. He watched her, found himself smiling, then jogged to catch up. She stopped outside the door, “There’d better be a tractor in here. Something with a motor. The hell kind of farm is this?”

She opened the barn. The dark inside made Calvin want to whimper. He didn’t want to go in. Now they were close, metal grinded on metal as the big blue light rotated. He didn’t like the sound. Or the smell coming out of the barn.

Emily sniffed. “Dead body,” she said, matter of fact.

“You watch too many procedurals,” he said, aiming for glib.

“I wish I had some of that stuff they put under their noses.” They stood shoulder to shoulder, staring into the barn. “How’s your phone battery?”

“Almost gone,” he said.

“You get to go then. We need one phone to call for help.” She laughed.

He glanced at the face, battery at 10 percent. He thumbed on the flashlight app, shined it through the door, stepped inside. The ground crunched under his feet in a way that made him not want to shine the light at the ground. He moved the light around, expecting to see farm things. Hay. Shovels. He didn’t know what to look for, or where. He’d never been in a barn. But again, as with the house, nothing looked like he expected.

He would not have imagined the dark splatters covering the walls, nor the giant meat hooks hanging from chains high overhead. The vast floor of the barn was clear, no boxes or tools. No tractors. No beat-up trucks. He made himself walk to the side and peered into what he assumed had been a horse stall. The splatters covered almost every space. A pile of something occupied the back corner. Maybe it was a dead animal. His stomach clenched at the smell.

He felt the air move, heard a rustle, a jingle, and something landed on his head. He dropped his phone and reached up like he’d walked through a spider web. His hands found something soft and warm, and it jingled when he pawed it. He grabbed and pulled, then screamed as sharp points of pain bloomed around his scalp. He tugged and the pain dropped him to his knees, sharp as it tightened. He turned to run, smashed his face into the wall and dropped.

He sat up slow, felt his head. He pulled down part of whatever it was … a flap of leather, bell on the end. A jester’s hat? He felt a stream of something run down his forehead, over his eye and down onto his cheek. He wiped at it with the back of his hand, then took a couple deep breaths, only then thinking to look up.

When he did, he noticed more detail in the space. Maybe his eyes were adjusting. He wished they hadn’t as he glanced around, thinking he was standing in the middle of an abattoir. He grabbed his phone. The screen had cracked. Part of the cap flopped forward and jingled.

“Calvin!”

He blinked. Oh, right. Emma.

“Calvin! Dammit, get out here. I think I saw another one!”

He trudged toward the door, exhausted. He stepped out into the mist.

“What the fuck? What happened? Jesus Christ, Calvin. You’re covered in blood.” She reached toward his head.

“No!” His voice reverberated off the buildings.

She jerked her hand back. He didn’t like the look on her face.

“Sorry. It won’t come off. I tried. It feels like it just digs in deeper.” He had a headache coming on, could hear his heartbeat like a drum.

She stepped closer, wiped off his forehead with the heels of her hand. “You okay?”

He nodded. “You saw another one?” And then, without looking where she pointed, he knew there were seven in a loose circle, and others, watching. He could’ve pointed to them, even though he couldn’t see any.

“What do you think?”

He realized she’d been talking. “Sure,” he said, brain catching up. “Let’s go check.” He took her hand and she lead him to the first of the chicken houses. He didn’t look for clowns because he knew they weren’t moving. Something made him look toward the road. The beacon grinded around, adding color to the landscape. He thought he heard something that wasn’t a jingle.

“You hear that?”

She paused with her hand on the door handle, shook her head. “No. What is it?”

“Not sure. Maybe a motor?”

“It’s probably a goddamn clown car.”

He laughed, and a tightness in his chest loosened. He pulled her into a hug. The moment stretched. He leaned in to kiss her. She put her hand to his chest.

“Not with that thing on your head.” She reached up, tugged on it. He hissed in pain. “You look like the jester at the Red Wedding. Let’s get inside.”

He kissed her cheek, then pulled open the door. He got a whiff of the same metallic rot from the big barn. “Em, we might not want to …” But she’d already started, her phone light ahead of her. She froze, half in, half out of the building.

Row after row, line by line, stood clowns. Tall and short, wide and thin, their eyes reflecting back red . They did not move, but shifted in their spots, as though on the verge of action. Then, they smiled at Calvin and Emma.

Calvin smiled, too, though it felt like it was someone else’s mouth. Emma back peddled, knocking into him, both of them to the ground. He landed on his back, Em on his chest, his hands on her hips. He inhaled the scent of her. She smelled good, like prey.

Emma thrashed in his arms, kicked the door closed. “Holyshitholyshitholyshit,” she said.

“You smell fantastic,” he said.

She rolled off him and onto her feet. “What the hell,” she yelled, smacking him in the chest. “Calvin? What’s the matter with you?”

His eyes flickered toward the chicken house. “They’re waking.”

She looked from him to the door and back, then stepped away. He smiled. She said, “Don’t you fucking smile at me, Calvin. It’s creepy!”

“I’m not trying to smile at you!”

She raised the tire iron like baseball bat, two hands at the bottom, left elbow pointing at Calvin’s heart. He heard the sound from the road again, and this time, turned toward it. The big beam of light swung by, and out on the road, maybe a mile off, he saw headlights. He pointed.

“Em, do you see it?”

She stepped back, looked at him, then turned her head to the road. Part of his mind thought, now.

“See what?”

“There’s a car.”

She shifted on her feet, raised up on her toes, looked to the road. “I don’t see anything.”

He knew, though he could not say how he knew, that were he to touch her, she could see. He stepped closer. “Let me show you.”

She put more space between them.

“Calvin, I love you, but you’re freaking me out. And stop fucking smiling!”

He felt a tear form in his eye, roll down his cheek. “I am not trying to smile at you. There is a police car out on that road looking for us. If you just let me touch your shoulder, I can show you.”

“Calvin, you are not making any sense.” And he could see tears in her eyes.

He stepped closer, offered her his hand, which looked brighter even in the wan light. “Take my hand, please.” Out in the dark, he could feel the seven watchers, though they did not move. Nor did the legion inside the chicken house. He could, if he concentrated, hear them. “Please, Em.”

She lowered the tool, said, “Goddammit, Calvin. What the hell is going on?”

He left his hand outstretched, but kept watching the car. He felt her move, felt the warmth of her fingers as they wrapped around his hand.

“You’re so cold,” she said, then “ooooh,” and he knew she’d seen the car down on the road.

“We’re going to have to run for it,” he said.

“Okay.”

“Stay with me. Do not let go. I’ll get you to that car,” and he didn’t know why he was saying it, but it felt like the right thing to say. And wrong. They protested in his head.

He started toward the gravel drive. They walked, then increased their speed. He felt the seven begin to move. “Here they come,” he said, and then one appeared in front of them as though from a jump cut in an old movie. One breath, the drive was clear, the next …

Calvin lowered his shoulder and barreled into it, pushing it back and away from Emily. He heard her growl, something almost feral, then heard the wet smack of the tire iron. He kept moving, she still had his hand. They closed the distance to the road. Calvin thought the timing would be close. If they missed it … If only the driver could just see.

Another clown appeared, this one on its hands and knees. Calvin didn’t sense it, tripped over it headlong, dragging Emily with him, crashing into the dirt. He rolled over, bridged up to his hands and feet and crabbed backward, bumping into Emily who was starting to push up on her knees.

The six clowns stood in a circle around them. Calvin expected to feel terror, but he did not. He felt calm, in control, and an urge to join the circle.

“Calvin …” Emma said, voice quiet as she threaded her fingers through his. “Get up.”

She crawled to her feet, tugging him with her. The beacon’s beam passed them again, color of the world strobing. Calvin heard the roll of tread on the road behind him. His brain felt slow to process. He realized he’d turned to face Emma’s back but didn’t remember doing so, and wrapped his forearm around her neck. He heard her say his name, felt them approve.

His thoughts tumbled, vision flipping from his eyes to a view from the others. He could see himself standing there, Emma trapped in his grasp.

The beacon came around again, and just as Emma said his name for a third time, this one in anger, he said, “hold on,” and then they blinked, twice, and found themselves standing on the far side of the road. The police car slid to a stop in front of them, spotlight flashing their way, blinding their eyes.

Calvin held tight to Emma, leaned in, kissed her neck and said, “Stay in his light.” The officer stepped out of the car. Calvin watched him with both sets of eyes. The man drew a gun, pointed at them.

“Let her go!”

He did not. He watched the beam circle in its tower, knew how much time was left. He lowered his arm from Emma’s neck, hugged her. He inhaled the scent of her hair, the one that made him feel he was home. He kissed the back of her head, the bells of his cap jingling slightly.

The light of the beacon rolled over them, and as it passed, he felt himself go with it, catching one last glimpse of the scene from the eyes of the circle. He pushed her, and she stumbled forward until her hands landed on the white hood of the car. The officer swore.

Calvin was not there anymore. He stood across the road with the seven in the gravel drive, watching the officer and Emily. The man ran around the front of the car, put himself between Emma and the far side of the road, the only place his brain probably told him Calvin could’ve gone.

Emma looked across the space, met Calvin’s eyes, because she could still see him. He tried to memorize her face, which alternated colors in the lights of the patrol car. Her dark damp hair hung around her head. Her skin seemed luminous.

One by one the six vanished around him until he stood alone. He wondered what he looked like to her. He raised his hand to wave as he felt a pull in his stomach, as though his molecules were being granulated and pulled through a straw. Emma turned grainy, like the screen of an old television between channels.

And then Calvin saw only absolute darkness.

***

He stood in the dark beside the road. Two jumps away. The water felt cold, but he didn’t mind. Nor did he mind the bugs in the air, or the worms he could hear squirming beneath the water and soil, safe underground. A thought of a woman, lithe with dark hair and eyes passed through his mind, and he felt … loss and sadness.

But he smiled and waited. Another would come and he could fulfill his purpose. He smiled into the night, into the fog and rain and mud, and he waited.

-

Cul-de-sac

Cul-de-sac

Jim didn’t trudge on his route. Trudging might indicate he didn’t enjoy his job. He loved the walking, the fresh air, the wind, sleet, rain and snow. He even didn’t really mind the dogs. Most of all, he loved the solitude and the freedom.

He didn’t miss desks. No TPS reports. No micromanaging or awkward break room conversations. He didn’t even mind the uniform, and the bag slung across his chest with its sturdy leather strap was the best he’d ever owned.

He smiled on the inside as he walked, headphones on, a special AI-curated Halloween playlist buzzing in his ears. Around him, the blustery wind shook the trees, streets still damp from earlier showers. There was the promise of a cool evening, the air tasted clean and crisp. Jim breathed in as much as he could, let it out in a slow, steady trickle.

He made the corner of 55th St., deposited a small box on the Taylor’s doormat that looked like a street grate with a creepy clown beneath it. At the Redman’s, he dropped letters through the slot, along with a couple Milkbones for Fletcher, their Jack Russell who bounced up and down behind the door, intermittently peeking at him through the door’s window panes.

Ahead of him, kids in costumes raced from porch to porch, little cabals of super heroes and monsters. He noticed they avoided the house at the end of the cul-de-sac. Mr. Smith’s house, a boring, red-brick home with weathered black shutters, black trim, and a small front porch full of cobwebs, curtains behind windows occluding any view of the inside. Never a car in the driveway, but the lawn was always mowed.

He’d never actually seen Mr. Smith, now that he thought about it. And Mr. Smith only ever received the weekly junk mail. Never a bill. Never a letter. No postcards or packages. If anyone asked, Jim would be hard-pressed to remember ever stepping onto Mr. Smith’s porch, even to deliver the Wednesday coupons.

Jim stopped and watched the children avoid it. They didn’t seem to discuss avoiding, but their groups skipped from the house on one side of the street straight to the other. It made him laugh, and remember Halloweens from his youth. There were always houses you skipped, always dark streets you sprinted rather than strolled.

He trooped up a driveway, filtering the letters in his hand for the Moyers, the last house on the right before Mr. Smith’s. He dodged a gaggle of big kids in last-minute costumes before stepping onto the porch. Ms. Moyer, whom he’d shared many a superficial greeting, smiled at him. She wore a long, black sparkly dress that pooled on the ground around her feet, a tall, pointy witches’ hat on her head. She opened the door as he extended her mail.

“That is a nice costume,” she said.

He smiled. “Worked hard on it. Totally authentic.”

She took her mail from his hand, replaced it with a full-sized Snickers. He smiled and nodded, thanked her.

“Make good choices!,” she said as he walked off across her lawn, slipping the Snickers into his jacket pocket.

As he stepped from the curb, he reached in his bag for the next batch of mail. On top was a weathered looking No. 10 envelope, corners bent, with a diagonal crease running from a top corner to the opposite bottom. Mr. Smith’s name and address were scrawled across the front, almost from one side to the other. No return address.

Jim stopped in the middle of the street staring at the letter. He had no memory of loading it into his bag.

“Huh,” he said, to no one in particular. He looked at the unremarkable house. Behind him, to the west, the sun had finally slipped below the horizon, turning the sky dim, transforming the trees to silhouettes, houselights to beacons of orange. The wind trashed the trees, the sound of crashing leaves almost louder than his music.

He headed up Mr. Smith’s driveway, scooted down the sidewalk, onto the porch, and lifted the hinged lid to the mailbox, which screeched as it moved. As he stepped back, he noticed the front door open behind a glass storm door. A tall, thin man with a long, sharp nose, bright blue eyes behind round, black wire-framed glasses stood staring at him. The man’s black suit, white shirt and black tie made Jim think of a hitman, or an undertaker, maybe the owner of a bookstore. The man behind the glass smiled, of sorts. It didn’t reach his eyes or show any teeth.

He creeped Jim out.

The storm door pushed open. Another not smile.

“Jim, yes?”

Jim nodded.

“We’re in a bit of a … predicament. Do you think you could come inside and help us?”

The man stepped out onto the porch, holding the door open with his back, motioning Jim inside with an expansive sweep of his left arm. Jim stared at his hand, then looked back to the fake smile.

“What sort of help do you need?”

“I’ll explain as we go, but trust me, time is of the essence, and the safety of the world is at stake.”

Jim exerted will to not roll his eyes, thought maybe Mr. Smith was delusional and might be in actual need of help. That or it was a heck of an elaborate Halloween prank. Despite the quiet, voice saying, “Dude, what are you doing?” in the back of his head, Jim stepped into the house.

The man closed the door behind them.

Jim glanced around, noticed a reddish orange glow coming from deeper in the house, but the rest of the lights were out. The air smelled of sweat and incense, and as he shuffled his feet, the scuffs echoed on the walls.

“If you’ll come with me,” the man said, then strode toward the glow. Jim took a breath and followed. They passed through what Jim assumed was the living room, complete with and old, cold, rock fireplace and no discernible furniture. They stepped through a sliding glass door and down into a high-ceilinged, rock-walled room.

In the middle of the space, five men sat at equal distant points around a glowing red circle. One of the men wore a brown terry cloth bathrobe. Another, what looked like graduation regalia. A third wore a blue and white Hawaiian shirt with giant hibiscuses all over it. The fourth, khakis, loafers and a muted pink polo shirt. The fifth wore a black suit, white shirt, black tie, and looked the twin of the man next to Jim. All were thin, almost gaunt, with sunken cheeks and dark eyes. They murmured together in an almost discordant chant.

One of them, the one in the bathrobe, appeared somehow worse than the others, his skin pale, almost gray. His body shuddered as he breathed.

In the middle of the circle stood a figure, vaguely human in shape, but its lines blurred, shifted as Jim stared at it. White eyes in a flaking black face stared at him through a soft column of pale red light.

Jim’s brain screamed at him, gibbering like a monkey in a zoo. He took a step back. Another.

“Jim, what do you know about magic?”

Jim swallowed to wet his throat. “Other than it doesn’t exist?”

The man in the suit gave the smile again. “That,” he said, and pointed to the thing in the circle, “is unimaginable evil from beyond our world. We have it contained, have had it contained, for decades. Were it to escape, our entire existence would be doomed.”

Jim, feeling a tad steadier, nodded along.

“We five are all that stand between it and our collective oblivion.”

Feeling better still, Jim said, “Sure. And it looks like you’re doing a great job. I’m going to go ahead and get back to my route.”

“Do you see the ill-looking gentleman in the bath robe?”

Again, Jim nodded, considered himself master of witty repartee.

“That is Mr. Smith, the owner of this domicile. At any moment, perhaps his next breath, he is going to pass from this world, and the circle will be broken. We have moments for someone to assume his spot, to maintain its integrity. Will you help us?”

Jim nodded, then, “Wait, what?”

“We need you, Jim, to help us save the world.”

“Who are you people?”

“We are masters of the arcane, stewards of the forbidden knowledge, keepers of the gates.”

“And what happens if Mr. Smith dies?”

“You are being obtuse. Assist us or … calamity.”

“You are a bit melodramatic.” Jim stared at the thing in the light, considered his options, considered the absurdity of the moment. “What do I have to do, and how long is this going to take? I have to finish my route.”

The man in the suit smiled, an actual smile, and his shoulders dropped. He said, “Open your mind, and hear my words. Mark them to your memory for all time, and may your will never falter,” and then the man’s words shifted to a language Jim had never heard before, not even in grad school. They circled and swooped round his brain, behind his eyes, and down this throat, through his body, and emerged from his mouth, filling in the proper spaces left by the men around the circle.

The man in the suit listened to Jim for a moment, then turned and walked around the circle to his twin. He met Jim’s eyes, motioned to Mr. Smith and his dirty bathrobe.

“Quickly, he hasn’t much longer. Be ready to assume his place.”

Jim stepped behind Mr. Smith, and as he did, he realized the words coming from his mouth synced perfectly with those of Mr. Smith. He tried to pause to listen, to be sure of what he was hearing, but the sounds didn’t stop, did not respond to his will.

He looked across the circle to the man in the suit. The man stepped forward and sat down, into his twin, the two figures becoming one. Jim tried to say, “What the h …” But his words could not overcome the murmured spell.

And then Mr. Smith collapsed, backward, his body withering to a husk in moments. Jim considered running again. The man in the suit motioned for Jim to sit.

Jim lowered his mail bag to the ground, sat, cross-legged.

The thing in the column loomed over him, its burning skin flaking off, falling ash, which Jim could now see piled along the edge of the circle in ebony drifts. He looked up, into the deep, white, endless eyes of the thing, watched as another piece of its face peeled off, floated down like a black feather, back and forth in an infernal wind. The ash settled on Jim’s forehead. It felt warm and soft, then hot.

Jim tried to scream. The thing looked down at Jim’s mailbag, which sat across the boundary of the circle, and smiled an endless white smile.

The end of the world screamed. Jim heard the sound in his soul, with his heart. The murmured words vanished from his mind, and he watched as the thing lashed an arm at the guy in the pink polo shirt. The man smashed into the wall.

Jim grabbed his mail bag and ran. He ran for the temporary safety, solitude and freedom of his route. He ran from the house at the end of the cul-de-sac that no one visited. He ran from the ash and screams and smoke.

And for the first time since becoming a mail carrier, he wished he’d kept his desk job.

-

Holiday Lights

(unedited)

The little gray plastic tab locking the screen in place didn’t want to cooperate. Connor stopped, glanced back over his shoulder. The loud voices seeped through the walls, beneath the small crack between the bottom of his door and the carpet, into his chest.

The cold wind rushing in from outside chilled his skin, a welcome respite from the heat of the house. A hint of fireplace smoke tickled his nose, the air otherwise crisp and clean.

The tab pulled loose. He started on the last one, bottom of the window’s left side.

The yelling from the front of the house stopped. Then stomping footsteps. The slam of the front door.

Then a louder voice, gruff, harsh, gravelly: “Merry Christmas.”

She’d gone, then.

He slid the window closed, moving slow and quiet, and sat back on his bed. He reached for The Swords of Lankhmar on his bedside table with his left hand as he pivoted, brought his legs up, settled them in place, and opened the book. He could almost read from the ambient light off the snow. But not quite.

He reached behind his head and flicked on his reading light, a flashlight with a long, flexible neck he’d duct taped to the back of his headboard. It created a small pool of wan yellow light you couldn’t see under his door from the hallway.

He tried to read, but the words fell away like water through fingers, thoughts a whirl of worry and anticipation. He wondered why they were fighting this time, on Christmas Eve of all nights. His favorite night. Usually.

He focused on the words.

Heavy footsteps down the hall, toward his door. They stopped, and he reached back to the flashlight switch, poised his fingers above it. The steps left, followed by the clicking of light switches and the flush of a toilet. A smoker’s cough, then the creaking of a bed.

He realized he was holding his breath. He waited 10 minutes. Then 20. He looked to his digital clock, which told him he couldn’t count, that it’d just been five minutes, so he started watching the red numbers climb up, minute-by-minute.

Time slowed, but Connor’s mind raced, a mix of where-was-she and what’s-under-the-trees, of guilt and excitement. He laid there, staring at the ceiling, imagining the floor he couldn’t see, where he’d left his rain boots, his coat. He planned his movements in order.

The house settled into its small-hours rhythm, creaking slightly in the wind, the heater kicking on and off, big, slow, warm breaths.

He waited and tried not to look at the clock’s glowing numbers. Then he gave up and climbed from his bed, going through the rehearsed motions. Jeans first, then socks, boots, coat, but not gloves. Back at the window then, he eased up the bottom half and applied pressure to the bottom middle of the window screen. It popped loose. He caught the bottom edge, pushed it the rest of the way out of its track, and lowered it to the ground.

Connor climbed through and down, to the snowy flowerbed beneath his window. He walked toward the middle of the yard with careful steps, the top layer of the icy-snow crunching beneath his boots. After 20 steps, he stopped and pulled in as big a breath as he could, then let it out in a flume, pretending himself an ice dragon. The stars twinkled overhead. The breeze whisked away some of the tightness in his chest.

North, across the big, winter-barren soy field, past the trailer park at the river’s edge, across the river and up the side of the rocky, steep hill, slow-moving lights of cars pulled across the distant highway. He imagined climbing the rocks, running through the trees topping the hills. He had a dark cloak, longbow, leather pack, and a sword on his hip. Running off to meet the elves.

There weren’t elves. He knew that. But elves in the woods probably didn’t worry about arguing parents. If there were elves in the woods, and they wanted him to go, he totally would.

Connor took another gulp of cold air and looked back to the stars. Sometimes, standing alone in his backyard as he often did, he’d see a comet. Once, he watched a big blue one travel across the sky, tail dragging behind it, fast, but slower than he thought a comet should move.

He thought about going to look for her. He’d done it before. Often. Sometimes, she’d just be laying across the back seat of the station wagon. Sometimes, the car would be gone. Others, just her. But tonight, for some reason, he didn’t go looking. He needed the night’s stillness, the silent, watching stars and the embrace of the cold. He often felt alone, but never at night, never under the starlit sky.

He felt the pull again, as he often did, toward the trees on that distant hill. To things that didn’t exist, that couldn’t, that only held to reality in the pages of his books. He had power there, amongst the ink and paper, where magic was real.

He sighed. Twelve years seemed too young to give up on magic, to give up on hope. But he wished it, for magic and wonder, for something other to be real.

Something high and to his right pulled his eyes. Straight down it fell, flame-flickering blues, greens, golds and reds, right into the trailer park. He expected an explosion as it crashed, but it vanished. Seconds ticked by, then it reappeared, hopped to the next trailer. One by one, it hopped between the flat roofs, left to right in his vision. At the end of the park, it turned and bounced to a house along the road, the first in the subdivision.

“What the …”

He wanted to move, but moving felt … wrong? He turned, still carefully, 90 degrees to his right, and watched as the fiery light hopped from one house to another down his street.

Then it was at his next-door neighbor’s house, its light so bright it was like looking right at one of those giant, blooming Independence Day fireworks from the town display. Multicolored shadows, it sizzled and popped as it vanished down the chimney.

Connor released the breath he’d been holding, again.

The lights popped up, then rushed toward his house. They flickered and crackled, popped like an kaleidoscopic campfire. The snow along the flue hissed as the light touched it, slithered between the vents and flowing down into the chimney.

It was in his house.

Again, his mind raced. Actions suggested and denied. Scenarios playing in trees of choices.

When the light began rising from the flue, Connor stopped thinking and said, “Wait.” By then, the light had coalesced back into a whole of sorts, and halfway in between its next bounce, at the edge of Connor’s roof, it stopped.

He did not see a figure. No person, no elf. A ball of prismatic fire that made him think of the lights on police cars. The light turned toward him, and then hopped off the roof, landing right where he’d stepped from his bedroom window. It bounced from snowy footprint to snowy footprint.

It reached Connor, circled him on the ground, pulling behind it a warmth Connor felt in his mind and to his bones more than along his skin. The light floated to eye level. Inside, he could see a small figure, clad in red armor over darker red fabric, a heavy red cloak hanging from its tiny shoulders, a tiny broadsword from its hip, its eyes points of red and green and gold and blue sparks inside a blazing white ball where its face would be.

It felt fierce and wild and powerful.

Connor could not speak, but fear did not grip him. And then he heard words inside his head.

Do not give up hope. It exists, and you will see it.

The figure backed away, jumped to his roof and stopped. He felt the weight of its attention on him again.

All will be well.

And then it hopped to the next house, and then the next, working its way down the street, through his neighborhood.

Connor stood still, but followed, watching until the light zipped back into the sky, trailing off to the west and vanishing. He closed his eyes, stretched out his arms and breathed. Lightness enveloped him and he found himself smiling. He could still hear and feel the words in his mind.

He stood in the yard until the feeling dissipated, though his chest felt loose and light, mind calm. Connor walked back to his window, clambered back inside. He reset the screen and closed the window. He pulled off his coat, his boots and his clothes, and slid into bed, pulling his heavy quilt to his chin.

Down the hall, across the house, the front door squeaked slightly as it opened and closed. Pressure in his chest lessened. He did reach up and shut off his light this time. She’d check. Smaller steps down the hall this time, again stopping at his door. The knob twisted, wood brushing across the carpet as she pushed it open. Just a crack. Enough to peek. His eyes squinched almost shut, he could see the darker-than-dark gap between the door’s edge and the frame, but couldn’t see her.

The door closed. More sounds, her getting into bed.

The house creaked and settled into stillness and warmth. In the moonlight from his window, Connor looked around his room, the whole experience replaying on a loop in his mind. After a time, his eyes felt heavy, so he closed them. But he could still see the flickering lights. And when he dreamed it was of hope, and mystery and magic.

-

Tromp L’oeil

Year 1

Jack, the gallery owner, had left early. He’d said something about banks, taxes and traffic, grumbled, then stepped out the back door into the windy October evening. It was about half an hour until closing time, and I told him to watch out for the crazy drivers.

It’d been a slow day, so I’d spent most of it behind the keyboard catching up on inventory and getting photos of the new artwork up on our website. You’d think there’d be an easier way to do such things, but so far, the technology gods hadn’t provided it. I kept clicking and watching the clock. At five of six, I got up and started closing down.

I had all the computers off and was locking the front door when my phone rang. I dug it out of my pocket, looked at the face. Jack.

I answered, “Hey, what’s up?”

“I just remembered something. Someone might be coming by right after six to see the … after-hours collection.”

He paused, letting what he said sink in. I inhaled, nodded to myself. It had to happen sooner or later, I supposed.

“Okay. I got it.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah.”

“If you want me to come back and deal with it, I can.”

“No, it’s fine. Who is it?”

“Doesn’t matter, but he mentioned wanting to see the Angel.”

I winced. “Really? Did you try to talk him out of it?”

“Yes.”

I nodded again to myself. “All right. I’ll take care of it.”

“If you have any trouble, call me. Otherwise, I’ll see you in the morning.”

It’s not that I hadn’t shown the afterhours collection, mind you. It’s that I hadn’t done it by myself. I walked back and unlocked the front door, then headed to the fridge in back and got a beer. I popped the cap, then headed out to the wooden ramp leading from the upper gallery to the gallery floor. I leaned on the worn, wooden handrail.

About then, the lightshow started. We have a program that controls our lighting, and at six every evening, it sets the lights dancing throughout the gallery, alternately illuminating different walls and works of art, drawing the attention of passersby. We know it works because we have to have the windows cleaned twice a month to get rid of the hand, forehead, and nose prints.

Outside, leaves tumbled across the parking lot and the trees swayed, casting dancing shadows on the ground. I imagined I could smell burning pinion wood. The sky was cloudy, and the clouds had that ambient glow from the city lights. I couldn’t remember if it was supposed to storm.

I’d almost finished the beer when the doorbell rang and the gentleman stepped into the gallery. He wasn’t very tall, and had unkempt dark hair atop his head. He wore a black pea coat buttoned tight, dark pants and black leather shoes in need of a good shine. He tweaked the end of his nose and sniffed, then looked around the gallery, eyes following the lights. I wondered if he could see them yet. Probably not. It was early still, or late, depending on how you looked at it.

He seemed hesitant to step further into the gallery. I wondered how long he’d sat in his car getting up the nerve.

“Good evening,” I said.

He stiffened, then looked around, trying to find the voice. I walked down the wood ramp, moving slowly and trying to look unthreatening. Don’t want to startle the deer, do we? I stopped a body length away and introduced myself.

“What’re you here to see, specifically?”

He looked at me and said, “the trompe l’oeils, obviously.” And just like that, I didn’t like him. Tone speaks louder than words.

“If you don’t mind my asking, where did you hear about us?”

“Places.”

“Our darknet site?”

“I read that, yes. But I’d heard of this place before.” He paused, swallowed. “It’s all … true?”

I nodded.

He looked around the gallery and started, his body jerking like he’d had a spasm.

“Is there anyone else here? I was told this would be a private showing.”

“It’s just you, me, and the art.” I waited a minute for him to calm down, then continued. “You’re comfortable with our terms and the fee?”

“Yes,” he said, again with that tone.

I nodded at him. “Follow me. We’ll take care of the paperwork, and then you can get on with your … viewing.” I walked away from him, back up the wooden ramp, and behind the counter. Their eyes, and his, followed me as I unlocked the black wooden box. I found what I needed, closed it, and presented it across the counter, five overly large sheets of parchment with scrawling text.

“If you’ll just read through those and sign on the last one.” I said.

“Is all this really necessary?”

“It is.”

He sighed, but began reading. It takes longer than you’d think to read through five pages of overly foreboding calligraphic text. Anyway, I wasn’t in a hurry to get on with the next portion of the evening. He finished, looked up at me, and stuck out his hand.

“Pen.”

I handed him the black wooden fountain pen from the box. He examined it, looked at me. “Where’s the ink?”

“If you agree to the terms, sign.”

He put the pen to parchment, then hissed as the barrel of the pen bit into his fingers, drawing its ink. He grimaced, signed his name. A few dark red drops fell off the nib as he finished then handed the pen back to me. I scooped up the parchment and deposited it back in the black box, taking my time and trying not to think.

“Do you have the cashier’s check?”

He unbuttoned the pea coat and dug out an envelope. He slid it across the counter. I left it.

“What would you like to see first?”

“All of it. I’m paying you enough.”

That was true. I gestured to the paintings behind him. “Shall we start up here?” I walked him over to the wall, stopping in from of K. Henderson’s Licorice Allsorts. It seemed an innocuous place to start. He looked at me.

“So I just reach in?”

I could tell he was unconvinced, and perhaps thinking he was PT Barnum’s proverbial sucker, so I reached into the painting, plucked out an orange candy and popped it into my mouth. To the right of the candy jar painting was Girl with a Curtain, a small oil painting of a nude woman drawn in pencil, framed by white diaphanous curtains. The curtains moved gently in a breeze I could neither see nor hear.

He moved closer, reached slowly toward the girl. She shied away. He pulled his hand back and glanced wide-eyed around the gallery. I could hear the city sounds – bustling traffic, the scuffs of footballs on the sidewalks – emanating from Erica Norelius’ Walking from Chinatown. The sensation made me giddy, like the first time I read a Harry Potter book.

He walked away toward the wooden ramp. As we passed Joseph Crone’s While the Cold Night Waiting, the woman met my eyes, then turned away.

“Perhaps you’d like me to show you around?”

I walked him through the pools of rotating darkness around the gallery’s outer wall. The lights fell off us as we passed Terry Isaac’s Wolf in Snow, and the wolf’s eyes glinted in the dimness. We turned the corner and Jeff Ham’s Raven cawed at us and shook out its feathers, the red and orange sky behind it drifted by like colored clouds.

I almost ran into him as he stopped in front of Scott French’s The Voices of Silence. I’d read Scott’s narrative on the piece dozens of times, but I was always struck by the woman’s sadness, from her somber expression right down to her loose-laced combat boots. She seemed vulnerable, and like it had the first time I’d helped Jack after hours, it made me uncomfortable to see a man leer at her and her strange rack of horns.

She looked up at us, out at us, past us, then down and away, shifting her legs to preserve what little modesty she had left.

“How much for this?”

I quoted him the price. “She won’t be like this in your home.”

“And why is that?”

“This reality is localized to the Gallery itself. We don’t know why.”

“Whatever. I want the painting. It’ll do for a start. What else?”

“I’ll get it ready for you after we’ve concluded the evening’s activities.” My voice sounded too formal to my ears, and I realized I was a little angry. It was hard not to feel protective.

“Would you like to see the Angel then?”

“Yes.”

The Gallery effect was different for each painting, but nothing as dramatic as that of Juan Medina’s The Blind Angel. I walked him to the painting.

We stopped in front of it, and I heard his breath catch. He made a production of examining the work.

“It’s quite a remarkable painting on its own,” he said, and leaned closer. As he moved, so did the angel. She stepped down, first to the end of the frame, and then to the floor. Her alabaster skin glinted in the moving light of the gallery, and I tried to look everywhere but at her. Her wings flexed with her breaths, feathers shivering. The figures created first by Botticelli, Bouguereau, Canova and Rembrandt, recreated by Medina, watched the angel as she moved.

She didn’t speak, but moved her head, looking the man over. I clasped my hands in front of me and studiously looked everywhere but at him. Or her. Then she spoke:

“Would you see?” Her voice was the most beautiful sound I had ever heard.

“Yes,” he said, low and quiet.

She turned to the poster she’d emerged from, and peeled it back out of the painting, revealing a dark corridor, the light within flickering like flame. Stairs descended into the dark. She turned back to the man and held out her hand. He took it, and she stepped back onto the picture frame, and then through the doorway, pulling him along. I watched as they moved down the stairs and out of sight.

I waited, counting in my head. Like the last time, I tried to not imagine what was happening at the bottom of the staircase. I thought about my wife and child. I thought about tomorrow. I thought about the flickering light on the staircase.

Then the screaming started, and it continued for some time. I wanted to go do anything else, but Jack had told me to wait for the angel to return. And then she appeared from the darkness, and I couldn’t help but think about how beautiful she was. I felt her glance at me, despite the blindfold. I looked at the ground.

I heard her voice, and knew she would say just what she had the last time. “Would you see?”

“I would not.”

“Very well.”

She turned and closed the poster behind her, smoothing it out into the painted surface, and then she lifted her arms and again became part of the painting. My ears popped as reality reasserted itself on the gallery. The lights continued their dance.

I locked the front door, set the alarm and let myself out the back. I took a deep breath of the autumn night air. I could smell burning pinion wood from somewhere nearby. I needed another beer.

-

Employee of the Month

Tromp L’oeil, Year 2

The crash of the phone onto the wood floor woke me. I had that moment of wondering what the sound was, where the hell was I, what time is it, before my brain caught up. Even still, I sat up in the middle of the bed waiting for some kind of prompt.

The phone vibrated against the floor. It seemed to shake the bed. I snaked my arm between the bedside table, groping around, thinking spiders.

I found it. Jack. It was also 3:15 in the morning. I thumbed it on.

“What’s up?”

“The alarm went off at the gallery. Security called. Can you go over there?”

“Sure?”

“The Farm’s security guys have already checked out the space, and there’s no one there anymore.”

The anymore had a weight to it. Moreso than if it were said by someone who didn’t work at a place with our particular inventory.

He continued. “They said front door was shattered, and they boarded it up already, but they can’t tell if anything was stolen. Just go in and look around. Check the video recorder, too. Might need to delete something.”

“Okay. I’ll call you after.”

I sat there a moment, contemplating just going back to sleep. The bed was warm and the windows weren’t broken. I sighed, stood up, and started looking around in the dark for pants.

***

Twenty minutes later I pulled into the Farm’s parking lot.

A police officer stood talking to the shopping center security guy by a police cruiser, lights spinning blue and red shadows across the parking lot. The guy leaned against his truck, arms flailing in storytelling mode. I pulled in next to them, nodded through the window and got out. It was warmer than it should’ve been in late October, but leaves still rustled in a light breeze. At least it smelled like Fall.

“Went ahead and boarded up the door for you,” the security guy said, “but I didn’t go inside. I let Officer Jansen in.”

“Thank you,” I said, then turned to the officer and tried to look grateful. I think I smiled, no teeth, and offered my hand. He shook it. Solid grip that matched his posture. I figured him former military. “You the owner?”

“No. He called me.”

“Right …” he started, then paused, choosing his words. I thought he suppressed a shudder. “I did not see anything.”

I nodded and looked past him toward the gallery. The interior lights had turned off. The orange LEDs lining the front windows made the broken pieces of glass glow like cooling embers on the gallery floor and sidewalk.

“What did they break the glass with?”

“I didn’t find anything inside. Might’ve just been smashed from the outside with a bat or a rock or something. Kids, maybe.”

“Did anything look torn up?”

“Not that I could see.”

I fought the urge to poke at him, failed. “Anything unusual?”

He realized about then I was questioning him instead of the other way around. His mouth tightened in a grimace, lips vanishing. “No.”

I nodded. “Do you need anything from me?”

Ah, yes. Paperwork. I filled in the blanks, answer the questions, thanked them both for their time, then assured them I could handle the rest myself.

***

I pulled the car around behind the gallery and went in through the back door. I flipped off the storage room light and stood in the doorway, letting my eyes adjust to the dark. The light switches for the main gallery were up front by the counter.

I stepped into the gallery and paused. I smelled cigar smoke, and heard faint notes of blues to my left, seeping out of Jeff Ham’s multi-colored Mingus portrait. I ignored it and took five more steps further into the dark. Orange and white light from the front windows spilled back across the gallery floor and walls. I heard a distinct plink of a piano key to my right and looked up at Pamela Wilson’s The Lyric of Chimerical Solace. The piano player shifted her hips, hooped skirt rustling, and looked back at me, then played another note. I turned and headed the other way, walking the perimeter of the gallery.

I passed Scott French’s Nighttime Stories, the one with the nude girl with a schooner on her head riding a polar bear through someone’s bedroom. Did the polar bear have red on its muzzle? The girl on its back appeared to be sleeping, the small ship tucked under her arm instead of atop her head.

I rounded the corner to head to the front of the gallery and could hear the dust and wind blowing out of David Shingler’s palette knifed Chico Basin landscape, could smell the salty air from the trio of Brett Lethbridge paintings, their satin fabrics popping and snapping in the gusts. I ignored it all as much as I could. Another note from the piano echoed across the gallery, and I looked back at the player. She’d stood and turned, leaning back on the keys. She teased her hand across several of them and played another, eyes meeting mine. I looked away.

I kept moving, stopping in front of the door and looking at the spilled glass as the motion detector finally found me and light filled the room. The green haired child clown in Wilson’s Like Ghosts of Fish giggled and splashed water at me, and when I turned to look, returned a smirk and winked. It looked at me through its binoculars.

I took a deep breath. “You can come out now. The police are gone.”

I heard cardboard boxes tumble in the back of the storeroom where I had just been, and a few moments later, a tall, thin man in dirty black jeans and a stained white t-shirt, greasy hair parted to one side stumbled out. He looked like a junkie of some sort, and I knew him, though he’d been cleaner when last we met.

“Walter. What are you doing?”

He walked toward the Piano Player, never making eye contact with me. She was where I’d last seen her, leaning against the piano, the hoops of the skirt bulging out, arms crossed under her breasts, but she was looking at me, not Walter. She arched an eyebrow. I shrugged.

“I needed to see her again.”

“I thought you had decided against that.”

“I …”

I waited.

“I changed my mind.”

I sighed, and I overdid it, so he would hear.

“Walter, you don’t get to change your mind. It’s a one-time affair.”

He turned, raced across the gallery and slammed into me, pressing my back to the wall. I checked to make sure I hadn’t smashed into any of the paintings, then wedged my arm over and under his, pressing his chest back with my forearm.

“I changed my mind,” he hissed, enunciating each word, face inches from mine. Up until that moment, I’d planned on talking him out of it, planned on helping the guy out. I never liked giving them over to the paintings. It made me … uncomfortable. But I’d never had a client pin me to the wall, either.

“Get your hands off me right now, Walter.” I stared him down, noting his bloodshot eyes and how his chest was heaving. All that was missing was froth coming out of his mouth. I braced my heels against the wall, and shifted my weight slightly in case he didn’t let go.

He released my shirt, but didn’t move. “I’m seeing her,” he said, then turned and walked toward the piano player. She looked over his shoulder at me, stuck out her tongue, and then offered Walter her hand. It was uncanny. She didn’t become more real, but maintained the tone and texture of the painting, and yet there was weight and substance to her limbs. The light on her did not look right.

Walter took her hand, placed one foot on the bottom frame of the painting, and stepped up. He became oil and tone and texture. His feet pressed down on the carpet, his legs displaced the hoops of her dress. She led him out of the room, out of my sight.

Nice knowing you, Walter.

***

The next half hour I kept my head down and cleaned up the mess. When I was all out of excuses not to, I walked back to the Piano player. I had to ask.

“Is he coming back?”

She smiled again. “The paperwork has been filled out. It is in the box under the counter.”

“And the fee?”

“Taken care of.”

Right. “Okay, thanks?”

“Would you like to visit one of the girls?”

“I would not.”

I turned and walked away, heading up the creaky wooden ramp to the front counter. Another of Wilson’s pieces, Pink Entropy, sat on the bar. The woman sat the antique black phone back in its cradle on her lap as I approached. She looked as tired as I felt. I wondered who she’d called, then laughed. The dog huffed a muffled bark at me, then licked its chops.

I opened the Box, and took out the fresh set of parchment on top. The bloody signature still glistened in the yellow gallery light. The red letters, which looked as though they’d been written by a frightened third-grader, read Walter Havershim.

I dug out the lighter we use for incense and heated up the black wax stick. I let it drip a puddle on the document next to Dwayne’s signature, then used our wrought iron LG stamp in the wax. I blew to cool it, started to put it back in the box.

The ramp creaked and a man strode up it. The hair stood up on the back of my neck. He was not tall, nor was he short. He was textured. His body was hung with an old school brown suit, complete with silver pocket watch hanging from pocket on a red satin vest. His shoes gleamed in the dull light, as did the thick silver rings on his fingers. A black bowler had sat crooked on his head, and tufts of dirty blond hair stuck out around his ears and neck. His skin was pale, teeth bright as he smiled at me. His eyes were an almost iridescent blue.

“I’ll take that,” he said, and held out his hand.

I looked down at the document in my hand, then at the box, and felt my face heat up. I may have gulped, but I did not shiver.

I held out the paperwork. He snatched with thumb and forefinger on his left hand, made a production of reading the pages, then folded and creased the parchment with a practiced motion. They vanished inside his jacket.

He offered me his right hand. “I don’t believe we’ve met.”

I shook it. “I don’t believe I want to.”

He didn’t let go. The skin was smooth as an infants, but cold, the shake firm, like he could crush my bones. He said, “Nonsense. You’re my employee of the month.”

I felt sick. “What?”

“Employee of the month.” He smiled, all teeth, and I noticed the canines were pointed. “You know, that cheesy award they give out for the month’s best performer? That’s you, boy. Employee of the Month.”

My brain started doing math. “But we’ve only had … six, maybe seven this month? Aren’t there warlords in Africa doing better than that?”

“It’s not always about quantity, is it? Wouldn’t you rather sell one $30,000 painting than a bunch of $1,000 ones?”

I shut my mouth.

He reached inside his jacket with his left hand and pulled out a small silver pin, some sort of sun with a broadsword pointing down through the middle of it. He turned my right hand, which he had not yet relinquished, palm up and placed the pin in the middle of it. It was almost uncomfortably cold against my skin. He closed my fingers around it, finally letting go.

“I’m not really … comfortable with this work.”

He arched an eyebrow at me, tilted his head. “Do you really believe that? Do you not think that each one of our guests gets exactly what is coming to them? Did our boy Walter not deserve his second visit?”

“I don’t know. I’m not a judge. I don’t know about his life, what brought him here.”

“Ah yes, but I do.”

I stood there, eyes locked with his, afraid or unable to look away. I had nothing to say. I had the feeling I didn’t want to anger this man.

“Good! I’m glad we’ve come to an understanding.” He fished the pocket watch out of his vest and checked the time. “I have to be off. Keep up the good work, and remember, I’ve got my eye on you. Let me know if you’d ever like to advance your career.”

He turned and walked down the ramp, whistling to himself. I never heard any of the gallery’s doors opened, but I knew I was alone in the building. I shivered, then locked up and went home.

-

Mrs. Cottingley’s Big Day

Author’s Note: I wrote this somewhere between 2003-2005. Don’t really remember when for sure, and I’ve had it stashed in my cloud for years. Found it again looking for a Halloween story to hang up. Reread it, and … I kinda like it. Knowing what I know now about Urban Fantasy … I wish I’d tried to get it published. Alas.

Mrs. Cottingley was 103 years old and ready to go. Maybe tomorrow. Each day was much like the next at her age, and she thought she’d made up her mind. As such, she’d gotten up that morning and set about putting her affairs in order. She had family to think about, after all.

There was her son and his family and her daughter and her family, both back in London and doing well. She’d take their weekly calls and occasionally get post cards and such. They never sent e-mail, which irked her because she loved her computer. Then again, she wasn’t sure they even had computers.

She tottered around the house in her baggy Gap jeans and a fuzzy pink sweatshirt, sipping a Bloody Mary and humming “Enter Sandman.” Her dog, Tinkerbell, a 22-year-old mastiff with a mottled black coat and flat teeth, sat on the sofa and alternated between watching the small woman teeter back and forth across the front room and the “Westminster Dog Show” on Animal Planet. Occasionally, Tinkerbell would sigh or mash the remote with a large paw to change the station to the Weather Channel.

The dog had just done such a thing when Mrs. Cottingley shrieked from the hall closet. Tinkerbell sighed, climbed down off the sofa and went to see check on her.